One of the stocks on my watchlist is currently experiencing its biggest drawdown since 2008, so I thought this would be an appropriate time to pitch it. This write up is longer than usual because I believe you, the reader, deserve a detailed analysis especially given the size of the company. I genuinely like LVMH. If I were to make a list of the top 25 highest quality businesses in the world, I think LVMH would easily make the top 12.

Business overview & Recent news

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton is the world’s largest and most influential luxury goods conglomerate. Headquartered in Paris, France, the company was created in 1987 through the merger of two storied French businesses: fashion house Louis Vuitton and wines and spirits producer Moët Hennessy. The group has since evolved into a global empire of prestige, overseeing a portfolio of approximately 75 high-end brands across sectors such as fashion, jewelry, cosmetics, watches, wines and spirits, and selective retail. As of 2024, LVMH operated more than 6,300 stores worldwide and employed around 213,000 people. LVMH reported €84.7 bn in revenue for the year 2024, with €12.6 bn im net income, reflecting the strength of its portfolio and pricing power despite global economic headwinds. These results demonstrate the continued dominance of LVMH within the luxury industry, even amid signs of slowing demand in key regions.

The first quarter of 2025 marked a period of normalization for the group following a post pandemic luxury boom. Revenue came in at €20.3 bn, down 2% compared to Q1 2024. Geographically, performance varied. Europe posted slight growth, while the United States experienced a modest 3% decline and Asia (excluding Japan) saw a sharper 11% drop compared to Q1 2024. This uneven recovery reflects shifting consumer sentiment and macroeconomic uncertainty in key luxury markets.

While Louis Vuitton continued to outperform with its blend of heritage and innovation, Dior posted more modest growth. In contrast, the wines and spirits division faced headwinds, with a 9% drop in organic revenue in Q1 2025. In response, Moët Hennessy announced a 10% workforce reduction amounting to about 1,200 jobs to improve cost efficiency and align staffing with pre-2019 levels.

Other divisions performed with more resilience. The perfumes and cosmetics segment remained relatively stable, buoyed by Dior fragrances and growing digital campaigns. Watches and jewelry saw slight growth, supported by strong performances from Tiffany & Co. and Bulgari. Meanwhile, the selective retailing segment, including Sephora and DFS, remained steady. Sephora continued to perform well in North America, while DFS still lagged due to the slow recovery of international travel retail. Strategically, LVMH is investing heavily in innovation and localization. It has partnered with Google Cloud to develop an internal AI platform called MaIA, which supports 40,000 employees in areas such as design, pricing, supply chain, and customer engagement. This digital transformation is part of LVMH’s broader effort to future proof its business. Additionally, the group is increasing domestic production of leather goods and jewelry in the United States to reduce reliance on imports and navigate rising tariffs and geopolitical tensions. While LVMH faces challenges, including a cooling Chinese market, rising global competition, and inflationary pressure, it remains well-positioned for long-term success. Its diversified business model, exceptional brand equity, and adaptability through economic cycles continue to set it apart. The group’s ability to fuse legacy craftsmanship with forward-thinking strategy ensures that it retains its leadership in the luxury industry.

History of LVMH

1743 – Moët & Chandon founded: The origins of LVMH begin with this iconic champagne house

1765 – Hennessy established: The renowned cognac producer that later merged with Moët & Chandon

1854 – Louis Vuitton founded: The luxury leather-goods brand that would become the core of LVMH

1971 – Moët & Chandon merges with Hennessy to form Moët Hennessy

1984 – Bernard Arnault buys Boussac (owner of Christian Dior), marking his entry into the luxury sector

1987 – Merger of Louis Vuitton and Moët Hennessy officially forms LVMH

1989 – Arnault becomes Chairman & CEO after orchestrating a takeover

1988–1997 – Series of acquisitions: Givenchy (1988), Berluti & Kenzo (1993), Guerlain & Céline & Loewe (1994–96), Marc Jacobs & Sephora (1997)

1992 – Opens first boutique in China (Beijing) and launches environmental department

1999 – Launches LVMH Tower in New York (Dec 8) and creates the Watches & Jewelry division; Sephora.com goes live

2011 – Acquisition of Bulgari (~€5.2 bn), strengthening its jewelry/watches division

2012 – Buys Loro Piana (€2 bn) and opens second Cheval Blanc in Maldives

2014 – Launches Fondation Louis Vuitton (Frank Gehry building) and acquires Rimowa (80%)

2019–2021 – Major expansions: Acquires Belmond (€3.2 bn) and Tiffany & Co. ($15.8 bn), launches Fenty fashion house with Rihanna (2019–2021)

Product Overview

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton owns a prestigious portfolio of 75 luxury brands, known as “Maisons,” spanning fashion, leather goods, wines and spirits, perfumes, cosmetics, jewelry, watches, and retail. Iconic names include Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, Tiffany & Co., Moët & Chandon, Hennessy, and Sephora. Each brand operates with a high degree of creative and operational independence, allowing LVMH to preserve their unique heritage while benefiting from the group’s global scale and financial strength. Below is a graph of the companies they own and some products they offer to the customer.

Over the last decade, LVMH has demonstrated robust and resilient revenue growth, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.7% from €30.6 billion in FY14 to €84.7 billion in FY24. The key driver of this performance has been the Fashion & Leather Goods segment, which grew at an impressive 14.3% CAGR, becoming an increasingly dominant contributor to group revenues. As of FY24, it represents 48% of total sales, up from 35% in FY14 highlighting LVMH’s strong brand equity in core luxury categories like Louis Vuitton and Dior.

Other segments like Watches & Jewelry and Perfumes & Cosmetics also posted healthy growth, with respective CAGRs of 14.3% and 8.4%. However, Wines & Spirits, grew more modestly at just 4.0% CAGR, and its contribution to total revenue declined from 13% to 7%. Meanwhile, the Selective Retailing segment (which includes Sephora) maintained stable growth (6.7% CAGR) but declined in percentage contribution.

Geographically, LVMH’s revenues are well diversified. Asia (excluding Japan) grew at 13.3% CAGR, rising to account for 28% of sales in FY24. Notably, Japan showed the fastest regional growth at 13.5% CAGR. The United States, another critical luxury market, expanded at 11.2% CAGR, representing 25% of FY24 revenues. Europe and France, while important, grew more slowly at 9.5% and 8.3% CAGR.

Moat (Competitive Advantages)

Brand Power: Perhaps the most apparent pillar of LVMH’s moat is its portfolio of luxury brands. Louis Vuitton, Dior, Tiffany & Co., Moët & Chandon, Fendi, Bulgari, and Hennessy are not simply labels. They are symbols. Brand power becomes a moat when customers demonstrate irrational loyalty. They return repeatedly, even when prices rise or competitors offer alternatives at a discount. In this respect, LVMH’s brands operate on a different plane than most consumer goods companies. These are not commodities. They are institutions. For LVMH, brand recognition is not achieved through volume or visibility alone. It is achieved through association with cultural prestige. Celebrities, royalty, and historical figures have long been linked with LVMH’s products, which in turn allows the consumer to feel as though purchasing a product is buying into an elite tradition. LVMH’s brands have become the default mental association with luxury.

Heritage and the Lindy Effect: Closely tied to brand power is the heritage of the brands themselves. Many of LVMH’s maisons were founded over a century ago. From an investing perspective, this longevity provides more than just historical interest. It illustrates what author Nassim Taleb has termed the Lindy Effect, the idea that the longer something has survived, the more likely it is to continue surviving. In other words, the durability of these brands is not a coincidence. It is a signal of staying power. Consumers subconsciously place more trust in legacy brands. A bag from Louis Vuitton does not just convey taste. It communicates timelessness. The brand has survived wars, recessions, and fashion cycles, and that durability becomes part of the product’s appeal. While competitors may try to enter the luxury market with new brands, they simply cannot manufacture centuries of prestige. This historical foundation creates an entry barrier that is effectively insurmountable in the short to medium term. From the graph below looking at what I consider the top 10 brands the average brand is 153 years old.

Psychological Moat Aspiration and Identity: Humans are social creatures who respond to status, aspiration, and belonging. Luxury products serve as identity signals. They are not purchased purely for function but for the emotions they elicit and the status they project. This is a classic example of psychological misjudgment working in favor of the business. People do not buy a four thousand dollar Louis Vuitton handbag because they need it to carry items. They buy it to feel successful, sophisticated, or admired. The desire to differentiate oneself from others is a powerful motivator, and LVMH has masterfully aligned its products with that deep seated need. Even looking at Ancient Rome purple-dyed clothing was so costly and exclusive that only emperors and high ranking officials were legally allowed to wear it. This vibrant hue became a symbol of imperial authority and divine status, turning a color into a political and economic power flex.

Pricing Power: Warren Buffett often emphasizes pricing power as the clearest indicator of a strong moat. The ability to raise prices without losing customers is, in his view, the hallmark of a great business. LVMH passes this test with flying colors.Its brands are able to raise prices frequently and meaningfully, often outpacing inflation, without eroding demand. In many cases, price increases enhance desirability. In luxury markets, high prices are not a barrier. They are a feature. They convey exclusivity and elevate the product’s perceived value.LVMH’s pricing power is further reinforced by its vertical integration. By owning its production and distribution channels, the firm maintains control over the entire customer experience. Unlike many fashion houses that rely on wholesalers or department stores, LVMH operates its own boutiques, ensuring that price integrity is maintained globally. This tight control supports both margins and brand equity, making pricing power a sustainable element of its competitive advantage. Moreover, LVMH’s core clientele, typically affluent consumers or middle upper class and are less sensitive to price increases. Their discretionary spending is more resilient to economic fluctuations, allowing the company to exercise pricing power in ways most businesses cannot. Altogether, this ability to charge premium prices and still grow demand is a cornerstone of LVMH’s enduring moat.

Cult Like Consumer Culture: Lastly, LVMH has succeeded in fostering a cult like culture around its brands. This is not accidental. It is the result of highly strategic marketing that blends tradition, storytelling, celebrity, and scarcity. From red carpet appearances to collaborations with pop culture icons, LVMH's marketing does not merely promote products. It elevates them to symbols of modern mythology. The result is a customer base that behaves not as casual buyers, but as devoted followers. They collect handbags like art, line up for limited edition sneakers, and share unboxing videos on social media as if revealing treasure. This deep level of engagement creates a feedback loop. Marketing builds mystique, which builds desire, which justifies premium pricing, which reinforces the brand’s exclusivity.

Management

Bernard Arnault, born in 1949, has orchestrated LVMH’s transformation from a modest luxury conglomerate into the world’s largest such empire. Arnault’s strategic vision shines in his skillful acquisition and revitalization of luxury brands from Dior, Celine, and Fendi to Tiffany & Co. transforming dormant labels into global icons. Rather than centralize control, Arnault experiments with a decentralized structure. Each brand operates autonomously under a mini entrepreneur like mode support. Arnault has steered LVMH through 2008's financial crash, the COVID-19 pandemic, and geopolitical strains like tariffs and China’s economic slowdown. His deep involvement reportedly inspecting store windows and visiting stores on weekends reflects his hands on leadership style

Despite his children, Arnault has yet to publicly appoint a single heir. In April 2025, shareholders approved raising the CEO age limit to 85 enabling him to remain at the helm potentially into his mid-80s.Bernard Arnault and his family own nearly half of LVMH’s shares around 48–49%while retaining approximately 64–65% of voting rights through their control of the Agache SCA holding company. This concentrated ownership is vital, it tightly aligns Arnault’s incentives with shareholder value and gives him the freedom to pursue long‑term strategies without short‑term market pressures.

First, ownership aligns incentives. With such a large personal stake, Arnault directly benefits from LVMH’s profitability and growth. He isn’t a mere steward but a deeply invested principal whose wealth and reputation depend on the company’s success. This alignment reduces agency problems commonly seen in widely held corporations and ensures that strategic decisions such as acquisitions, investments in craftsmanship, and brand positioning are guided by long-term value creation for the shareholder.

Second, voting control shields strategy from external pressures. Thanks to the layered holding structure Arnault and his heirs can make bold, sometimes unconventional choices (e.g., raising CEO age limit to 85, costly acquisitions like Tiffany) without risk of hostile takeovers. It also ensures continuity across generations; the structure legally prevents non family ownership and mandates unanimous sibling consent on major decisions, a mechanism designed to prevent fragmentation of control.

A third advantage is succession stability and harmony. Arnault has gradually inserted his children into executive and board roles Frédéric leads Financière Agache as managing director and oversees LVMH Watches; Delphine heads Dior; Antoine runs Dior SE; Alexandre and Jean lead roles at Tiffany and LV Watches respectively In essence, Arnault’s ownership and control incentivized him to sustain LVMH’s premium positioning, global expansion, and creative autonomy over decades. While investor concerns remain particularly about succession clarity his ownership structure provides a powerful alignment between his private incentives and the long term interests of all shareholders.

In short, I believe LVMH currently benefits from exceptional leadership under Bernard Arnault. That said, it would be naive to assume his successor will match his strategic brilliance and vision. Still, LVMH’s portfolio of world class brands is likely to continue compounding value over the coming decades. As long as the Arnault family maintains its significant ownership stake ensuring strong alignment of incentives I see little reason for concern about the company’s long-term trajectory.

Futhermore The Credit Suisse report “Family 1000” tracks ~1,000 public family-owned firms (20%+ founder stake) since 2006. They outperform non-family peers by ~300–400 bps annually, powered by stronger revenue growth, higher margins, disciplined capital allocation, conservative balance sheets, and long-term vision. Younger, smaller family firms show especially robust returns.

The Numbers, Valuation and Peers

LVMH has demonstrated a decade of strong and consistent financial performance. From FY14 to FY24, revenue grew from €30.6 billion to €84.7 billion, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of +10.7%.

Profitability has remained robust throughout the period. Operating income grew at a +13.2% CAGR, outpacing revenue growth, which highlights operating leverage and disciplined cost control. Free cash flow generation has been particularly impressive, compounding at +17.5% Free cash flow margins improved significantly, reaching 17% in FY24 from 9% in FY14.

Gross margins have consistently held between 64% and 69%, a reflection of the pricing power and exclusivity of LVMH’s brands. EBIT margins have hovered in the 19–27% range, while net income margins, although more volatile, remained solid, averaging around 13–15% in recent years.

LVMH has managed its balance sheet with care. Shareholders' equity has tripled over the decade to €69.3 billion, while total debt has also risen, though the company has maintained a conservative debt to equity ratio, typically between 0.6 and 0.7 in recent years. This suggests a prudent use of leverage to support growth without compromising financial stability.

Return on equity (ROE) and return on invested capital (ROIC) have been consistently strong. ROE averaged around 18% while ROIC remained between 13–17%, reflecting efficient use of capital and high returns across business lines.

As you can see LVMH is currently trading at a discount to its 10-year valuation averages. Currently LVMH is sitting at a P/E (NTM) of 19.3x. Although this is a large discount to their 10 year P/E of 24.1x I wouldn’t consider LVMH a screaming buy. I would consider it a buy though. The range where LVMH becomes a screaming buy is anything under 15x earnings.

Above is just a simple and quick back of the envelope valuation based on projected net income with a projected multiple. I simply took the 2024 net income and compounded it at a conservative +8% per year till 2029 and slapped a 15x multiple to represent the bear base, 18x multiple to represent the base case and 20x to represent the bull case. Keep in mind in the last 10 years the average P/E has been 24.1x and in the last 20 it has been 21.0x.

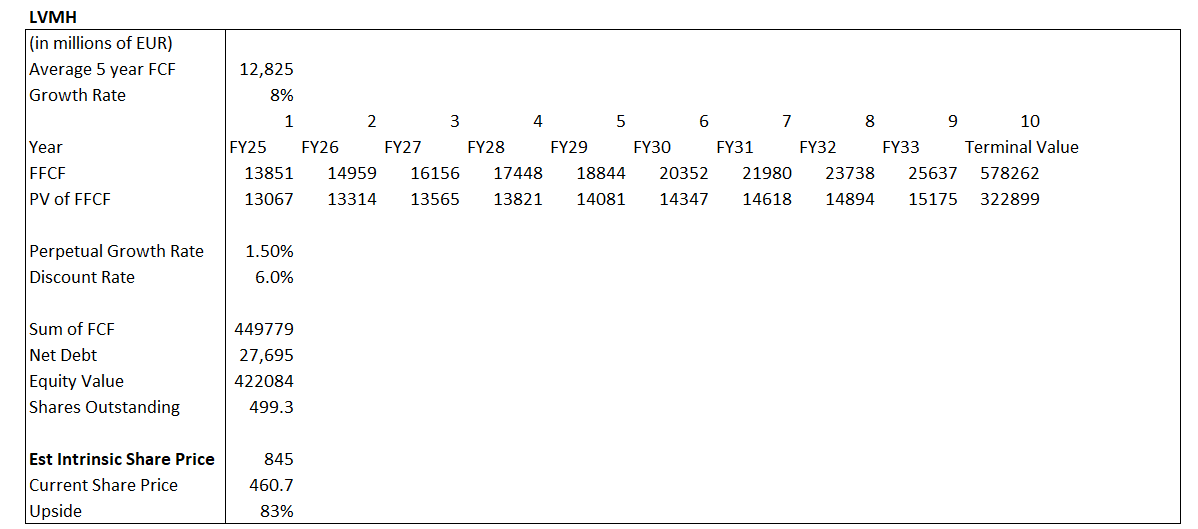

To estimate starting free cash flow, I used the 5 year average of €12,825 mn, which is more conservative than the 2024 figure of €14,209 mn. I prefer using an average rather than a single year to smooth out fluctuations and better reflect what the company might sustainably earn going forward. For the growth rate, I applied +8%, which I believe is a reasonable and conservative estimate based on LVMH’s past 10 year financial performance and the strength of its economic moat. The terminal growth rate was set at 1.5%, in line with long term developed market GDP growth, an approach that avoids overestimating value beyond a realistic horizon. For the discount rate, I used Joel Greenblatt’s 6%, which I view as a rational hurdle rate incorporating the long term return of U.S. government bonds plus an equity risk premium. After adjusting for net debt and dividing by the current number of shares, my estimated intrinsic value comes to €845 per share about 83% above the current price.

Regarding peers LVMH currently trades at a notable discount relative to its luxury peers across several valuation metrics. Its P/E (19.3×), EV/EBIT (14.1×), and P/FCF (18×) are all significantly below the peer group averages (33.8×, 23.5×, and 33.1× respectively), suggesting a valuation gap that may not be fully justified given its financial performance. LVMH also offers the highest dividend yield (2.7%), indicating stronger shareholder returns in the near term.

Despite the discount, LVMH maintains strong and consistent fundamentals. Its 5-year average EBIT margin (24.3%) is above the peer group average (+22.5%) and notably resilient. Similarly, its net margin (+15.9%) and ROE (+20.8%) also outperform the group, while its ROIC (+13.7%) is solid.

Futhermore, LVMH’s balance sheet is healthier than most peers, with a relatively low debt to equity ratio (59.6%) compared to others like Burberry (208.9%) or Brunello Cucinelli (190.1%). This gives LVMH more flexibility in capital allocation and downturn resilience.

In terms of growth, LVMH’s 5-year EBIT and FCF CAGR of +11.3% and +10.1% are respectable and well-balanced, especially given its scale. However not as high as Hermes. However Hermes is trading at over twice the P/E of LVMH.

I actually think Kering stock will actually perform better than LVMH in the short term simply b ecause of how cheap it is. For instance Kering is in a 75% drawdown from all time highs and is trading at 1.5x book value which is incredibly cheap for a brand like Kering. A large portion of Kering’s book value is tied up in premium real estate. If you strip out the value of those properties, you’re effectively valuing the rest of the business including brands like Gucci, Saint Laurent, and Bottega Veneta at just a few billion euros. That seems absurdly low for a portfolio of world class luxury names. However if i had to choose to buy either LVMH or Kering and hold for 10 years id buy LVMH since I personally think it's a better company.

RIsks

Succession Risk: LVMH’s long-term success has been closely tied to Bernard Arnault’s leadership. At 75+, questions around succession are increasingly relevant. While his children are being groomed for leadership, it’s uncertain if they will maintain the same strategic brilliance, discipline, and risk management that Bernard demonstrated over decades.

China and Emerging Market Dependence: A significant portion of LVMH’s growth—and luxury demand in general—comes from China and other emerging markets. If luxury spending slows due to economic weakness, government crackdowns on conspicuous consumption, or geopolitical instability, LVMH’s sales and margins could take a hit.I actually have a theory about why China loves luxury clothing. I've stated it before in a previous write up so ill quote it.

‘‘China has been a communist nation since 1949, and atheism has been strongly promoted by the government. Throughout history, every civilization has needed something to worship whether it was gods, emperors, or ideologies. After 1949, the void left by religion was filled by Mao’s Little Red Book, which became a symbol of national pride and unity. The Chinese population, deeply nationalist, followed it closely. However, after Mao's death, a shift occurred. With the end of a unifying ideological force, status began to replace worship. Fast cars, prestigious job titles, private schools, and designer clothing became the new objects of desire essentially, the new “religion” of China. This culture of status breed’s envy. And as we know, envy is a dangerous emotion.’’ - A Good Chinese Booze Company Trading Cheaper Than Its Peers Favona Hathaway

Podcasts

Song of the Week

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute financial advice, investment recommendations, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. You should conduct your own research and consult with a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions. The author may hold positions in the companies mentioned, but the opinions expressed are their own and are subject to change without notice. Investing involves risk, and past performance is not indicative of future results.